No, this isn’t a post about a New Year’s resolution, though what I say here will significantly impact this upcoming year.

No, despite the typical career transition sentiment of my headline, I am not leaving Orchestrate, the awesome company where I have worked since May to make developers more productive and creative.

This will be a personal post on what is still, according to the domain name, a personal website.

This is Hard for Me to Write

Seven and one-half years ago, I made a commitment to you.

I made a commitment to my country.

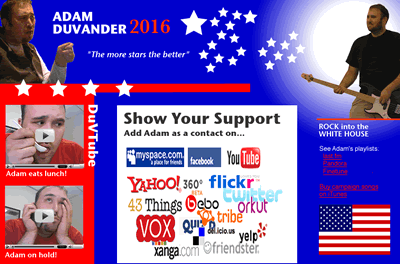

At a time when most were announcing two years in advance of inauguration day, I put my name on the line. On July 4, 2007, I started my campaign for president of the United States. For 2016.

A lot has changed since then. Most of the social networks on my campaign website are out of business or shadows of their formal selves.

A lot has also changed with me, but you wouldn’t know it from looking at this site, which again purports to be a personal website.

A Blog Divided Shall Not Stand

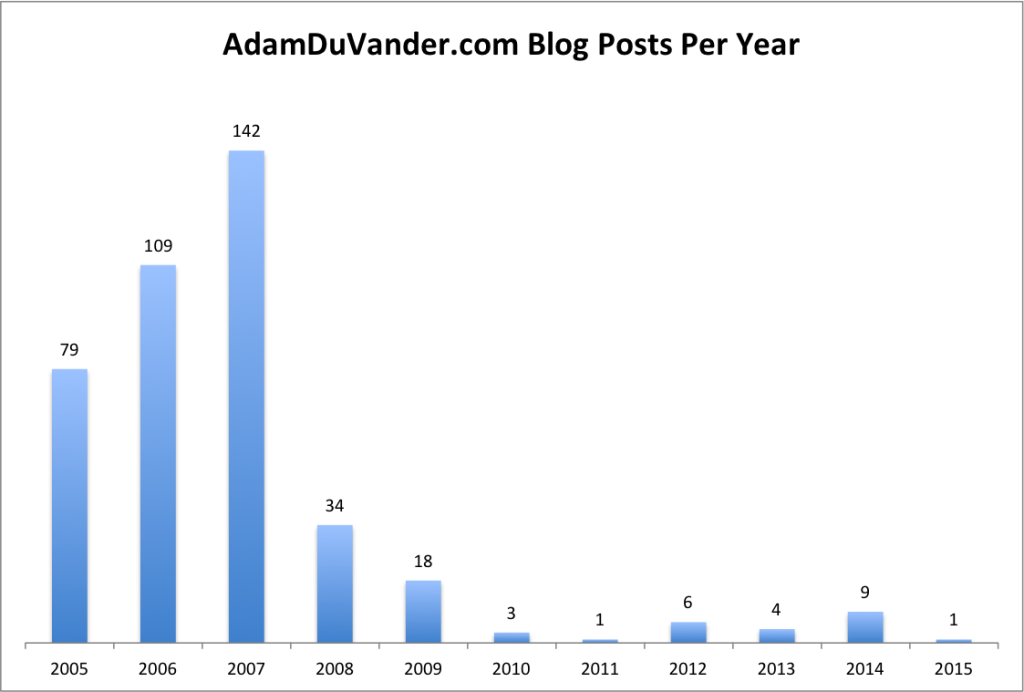

In 2008, I decided to stop programming and start writing about programming. In essence, I became a professional blogger.

And I’ve been one ever since.

Webmonkey, Wired, and ProgrammableWeb were all clearly blogging gigs. My last two roles, at SendGrid and now Orchestrate, there’s a lot more to it… but the blog has factored in pretty heavily.

It used to be I would write blog posts on this site with care. Sometimes I would include hand-crafted charts, like above. I would write about personal news and not just insights that fit the Simplicity Rules® theme.

Professional blogging and personal blogging are about as similar as cheddar cheese and head cheese.

Rambling into Revelations

In ignoring the personal side of this personal site, I have let major life developments go without coverage.

I got married. In 2009.

I am a father. We had twins, but they’re over two years old now.

I am impressed by my good friend Jacob, who blogged a two word entry about his son well before Gibson’s first birthday. The post headline begins, “a couple months ago,” which is itself commentary on today’s social web.

The personal website, whose death I lamented way back in 2007, still owns a warm place in my heart. Yet, now it has a companion in the hereafter that goes by the name “personal blog.”

I can’t completely bring them back, but I can do my best to honor them by announcing some personal news to this site:

As the headline suggests, I am going to spend more time with my family. For politicians, this typically means leaving office. For me, I won’t ever get there: I am suspending my campaign for president of the United States.

I am so thankful to have incredible support from my family: my wife Jenny, son Evan, daughter Alana and the new baby I am extremely excited to meet in June.

What? You didn’t think I was just going to post that on Facebook, did you?

By the way, to get back to the non-personal topics for which this blog is known, this post is an excellent example of burying the lead.

I’m a fan of

I’m a fan of